During the course of this evening’s conversation between David Mazzucchelli and Dan Nadel, the PictureBox publisher asked the artist what he learned from working in the superhero comic book medium during the 1980s. As you will read, Mazzucchelli believed that working at Marvel and DC taught him the importance of clarity. His appearance at MoCCAwas almost as rare an occurrence as a new Mazzucchelli comic, and it’s easy to understand why he’d prefer to limit his public exposure. Making sure that you’re not misinterpreted–reinforcing that clarity–can be hard work.

During the course of this evening’s conversation between David Mazzucchelli and Dan Nadel, the PictureBox publisher asked the artist what he learned from working in the superhero comic book medium during the 1980s. As you will read, Mazzucchelli believed that working at Marvel and DC taught him the importance of clarity. His appearance at MoCCAwas almost as rare an occurrence as a new Mazzucchelli comic, and it’s easy to understand why he’d prefer to limit his public exposure. Making sure that you’re not misinterpreted–reinforcing that clarity–can be hard work.

It was clear, however, that tonight was an event. MoCCA quickly ran out of chairs and the small gallery space on Broadway was filled with both fans and artists, among them Dash Shaw and Frank Santoro. Sitting at a table and beneath a lousy lighting system, Mazzucchelli responded to Nadel’s questions amid the sketches and pages which make up the exhibition Sounds and Pauses: The Comics of David Mazzucchelli, which runs at MoCCA until August 23. It’s a summer of Dave. His long-awaited graphic novel, Asterios Polyp, was published in the beginning of July.

It’s an extraordinary work, situating a vain architect in exile. After a cataclysm destroys his New York apartment, he jumps on a bus for anywhere. As an priapic academic and self-regarding husband, Polyp is no innocent. Once he settles in a small town, however, he begins to piece a new life together. Dreams situate him in the grand designs of predecessors like Piranesi. Flashbacks show how his marriage to the sculptor Hana–all anxiety and smooth lines to Polyp’s impassive, nail-like form–went awry. In-between, it could be said that Mazzuchelli plays games with color–a predominantly purple line separates into reds and blues–and flirts with both autobiography and art history. It’s not hard to imagine Polyp’s status as an architect whose work only exists on paper as analogous to a cartoonist, or his bemusement at a local punk group reflecting an artist appraising his position vis-a-vis against the underground.

During his interview, Mazzucchelli made frequent reference to his interest in space and the city. He also spent much of his time attempting to give as little away as possible. After the jump are notes which attempt to approximate his answers.

First, Dan Nadel asked him about the visual themes which appear in his work: an interest in landscapes and urban environments. How had his upbringing and movements around the world influenced that?

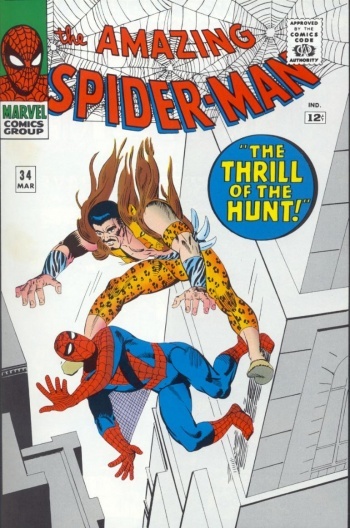

DM said he grew up in a small city, but that his childhood was spent in an environment not very different from Charles Schulz‘s world. Every house had a dog, a doghouse, and the dog slept on the doghouse roof. His interest in man-made spaces came through comic books, especially the work of Kirby and Ditko. These, however, were essentially unrealistic cityscapes. When he was in art school, he began to draw cities himself.

DN: Which made a bigger impression on him–the work of Kirby and Ditko, or the experience of an actual city?

Kirby and Ditko. It was only when he moved to New York and experienced it for himself that he realized a real urban space was not the same as a space created for superheroic activity. Superheroes could never do what they do in real urban space.

DN: How influential was his time studying at the Rhode Island School of Design?

At RISD, he had a brief period of being unsure about pursuing comics as a career. There he concentrated on the elements which would eventually abet his comic book art: figures, spaces, training, albeit in paintings and the like. But during the 1980s, making comic books was frowned upon by RISD. It was considered “slumming.”

DN: So why comics, then?

He had always made them. We can blame his older brother for encouraging his interest. What comics offered him was a chance to not only indulge his love of drawing, but also to tell stories.

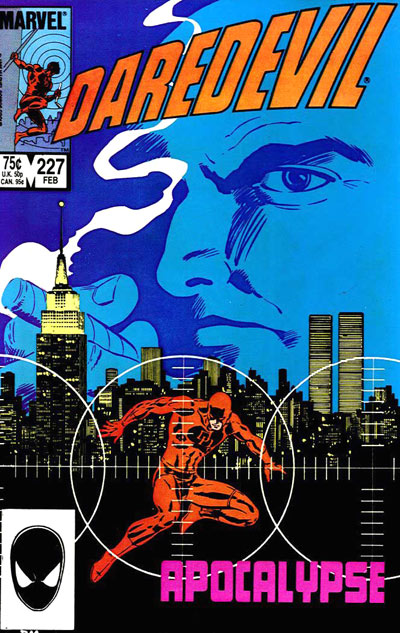

DN: What did he learn from superhero comics?

Working on superhero comics taught him about deadlines. Work needs to get done. Because of deadlines, inferior work will be printed. He also learned that the last person who gets their hands on the art determines what it looks like, whether it’s a colorist or an editor. Gradually, DM took steps to assume control over his work. He started as a penciller, then began inking his own work, and even got involved with some color. The old assembly-line model of mainstream comics taught him the division of labor. Paradoxically, DM began to think of comics not as a collaborative medium but a complete work. Once he left the trade, he felt like he had to unlearn the superhero “habits” of lay-out and that approach to drawing. Now, however, he doesn’t think he really need to unlearn that much. Mainstream comics was a great training crowd to perfect storytelling skills. The field is still oriented towards children, hence it’s necessary to emphasize clarity at all times to tell a successful story.

DN: Does he always have an eye on the reader/audience when he’s working? Or does he sometimes do things just for himself?

Comics are a medium of communication. It’s not an “either/or” proposition for him. He needs to enjoy it, but he also thinks about the reader. What he expresses must come across clearly where he wants it to be clear. But he also wants to make comics that he wants to read. That’s the starting point.

DN: While working at Marvel, did he look at other cartoonists? DN made reference to things DM had told him about Sternanko and Toth.

There’s no simple answer to that question. He looks at artists he admires, but can learn something from everybody’s work. He takes away lessons from different sources. “Oh, there’s a good hand.” He tends to lean towards the auteur creators when he wanted to start writing his own stories.

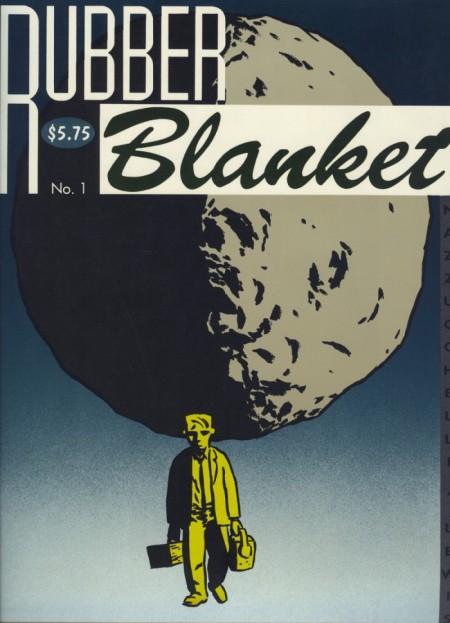

DN: Can he describe what led to the transition into Rubber Blanket?

When he left commercial work, DM didn’t really produce any kind of comics for a year. He needed to rethink what kind of comics did he like. He realized that the comics he had been working on were very different from the movies, novels and art that he loved. He took the time to explore underground and European comics. He started working on short pieces like “Near Miss.” He wanted to work in a different style and work in black and white. Using those two colors forced him into harhs, high contrast artwork. He went back to children’s books and textbooks which used black and white. He spoke about printing black ink as a halftone, although here I lost the thread a little bit. Then DM took a print-making class and learned how printing inks worked together. He wanted to make a magazine where stories could exist in a context that would help give them meeting. He and his wife chose the title Rubber Blanket from a term from offset lithography. A “rubber blanket” is the name given to the rubber coating given to a drum. The coat catches the ink and applies it to the paper. The title said that the “printing process is what this is about.”

DN: What did he learn from self-publishing?

That you had to have strong arms. There’s a lot of carrying stuff around.

DN: What happened to Rubber Blanket after the third issue?

DM noticed that the stories were getting longer and longer. They went from nine pages to 24 pages to 34 pages. He wanted more space and realzied the fourth issue would be one long story. That fourth issue turned into the 300-page Asterios Polyp.

DN gestured to pages from the “Big Man” story behind the podium. Could DM talk about how that came about?

Over several months, DM began drawing a giant figure in his sketchbook. He realized he needed to do a story. “Big Man” was an attempt to make a story with a fable-like structure that was nevertheless invested with emotional content.

DN: There’s a Chester Gould influence in Asterios Polyp, as well as nods to Kirby in “Big Man.” What does he learn from different artists?

DM is always looking to learn from others, but only tried to emulate one artist one time. This was a pastiche of Kirby’s work. (Not “Big Man”.) Drawing this made him feel like a 12-year-old again, although he could feel like he was getting a little closer that time. Then he went back to the Kirby originals and realized how short he had fallen. In his work, however, it’s always the story which dictates the approach rather than the need to tip the nib to a particular artist.

DN: What’s his daily routine?

DM laughed at this point. He said it was a strange question. It depended on what stage he was at. While working on Asterios Polyp, he spent many months of sketching and notetaking. During the mornings he would begin a writing and drawing session that ended when it ended. Work only gets done through the process of daily drawing. DM takes the approach of trying to do a page a day. If he can’t achieve that, he thinks he’s doing it wrong. But DM admitted that this goal, which probably grew out of his days working on mainstream comics, is rarely attained. He thinks the comic medium is nevertheless designed to be that quick. It stems back to the origins of the comic in the gag-a-day newspaper strip. There’s a routine to it. The aesthetics of comics are borne from the deadline.

DN: So how does he approach a 300-page book?

The first question he asked himself was what’s the easiest way to draw this book? But ultimately, “it was done when it was done.”

DN asked DM to expand on the construction of the book, and made reference to how Photoshopping helped him make the book in layers.

DM said that the computer allows him to work quicker in this regard. It eliminates his past need to use white-out or sometimes to snip panels out from the work and redraw. Scanning allows him to draw a good hand next to a bad hand, and then drag it over and replace the offending drawing. Gesturing to the artwork on the walls, he mentioned that you could find many of his fixes in the margins. Then he would drag them onto the work itself. The computer, however, doesn’t change how he designs pages. The computer let’s him tweak, but everything is planned ahead of time.

DN said that the linework in Asterios Polypfeels like a natural evolution, influenced by manga artists and Gould. Could he explain how his linework evolved?

This was probably the most uncomfortable DM got during the evening. He said he didn’t want to talk about it, and mentioned again “I try to allow whatever the story is to dictate the approach taken.” When he was working on superheroes, he strived towards the illusion of solidity. He used the aesthetic of film noir and shadows to make things look solid and emphasize shapes. As his work developed, illusionism became less important. The line to him is a kind of calligraphy. He was also interested in the same hand making the line and the lettering in comics. This influences how he approaches line and “mark-making.”

DN: Film noir was an influence on his adaptation of City of Glass. Was that still seductive?

Ignoring the question (or at least what I thought was the question), Mazzucchelli instead talked about art as the act of creating magic on the page. The page is always flat. But you can create marks five inch apart on that blank page and somehow create the impression of a third dimension. Comic book art can play with our appreciation of three dimensional space. He’s interested in depicting space on the page. This response seemed particularly interesting in regards to Asterios Polyp as an architect, who is also playing with creating a space on the page that then can be realized in real life.

DN turned the questions over to the floor. First up was Frank Santoro, who bellowed from the back that he wanted to know what kind of pen Mazzucchelli used.

DM uses different things. On Asterios Polyp he used calligraphy nibs. Previously he had been associated with the brush, where the thickness of the line was determined with how the artist drew it across the page. The calligraphy pens let him have an unpredictable thick-to-thin line which flattened the image.

Another attendee applauded his depiction of Polyp’s apartment, a view of which becomes a motif throughout the book. Could he talk about how he designs such a space and fills it with telling props?

DM asks himself, “Who lives here? What would this person’s space be like?” He starts with the character and then tries to think of a credible environment.

What kind of narrative models did he have for Asterios Polyp?

Here there was a long pause. DM couldn’t pinpoint a specific example. There were two important things which played into the creation of Asterios Polyp. The first was the decision to break the narrative into short chapters. That allowed him to see the structure of the book. The other breakthrough was the Greek nationality of the character. That allowed him to bring in The Odyssey as a touchstone. The rest of the work became a matter of problem-solving after those two things had been settled on.

His Batman in Year One seemed to have a much more realistic physique than most other superheroes. Why?

When DM was working on the story, Denny O’Neil brought him two giant folders with photocopies of the first years of Detective Comics and Batman. He used those as a visual reference and Bob Kane‘s original design was referred to. These first conceptions of Batman seemed highly stylized, at least to him. He turned to his art school training in realism. He wanted to draw “a real looking guy wearing this suit.” His aim was to make it “credible.” For this reason, he tried to depict a man who would be able to climb up the side of a building while still wearing a heavy cape and books boots. However, if given the same assignment today, he would do it differently.

What writers is he influenced by?

DM took this question to mean what were his reading habits. He enjoys the work of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, and another Latin American writer whose name escaped me.

Could he explain the origin of his Japanese pubic hair censor story, “Stop the Hair Nude?”

On his first trip to Japan, DM made friends with a French expat who ran a publishing house. He rented an apartment in Japan. In the post he received a brochure that read “Stop the Hair Nude.” In Japan, the depiction of pubic hair is not allowed. There are censors who usually blur the offending follicles or obscure them completely. However, lately exceptions had slipped through the net and a protest had been engineered to maintain standards. DM’s friend said that he had books sent to him in Japan. When he opened the package, he discovered that someone had scribbled out the pubic hair. These two events provided the inspiration for the story. Later, DM learned that most of the censors responsible for blotting out pubic hair in art, comics and films are actually middle aged women.

What is his favorite color?

He likes them all.

His work exploits the potential of comics and draws on manga, European comics and graphic novels. What are his current itches?

He doesn’t want to comment on what he’s working on now.

He has used black and white for years. Considering he just said he liked them all, does he want to explore color’s potential more?

It’s all about choices. There is more color than you think in Asterios Polyp–including the color of the paper.

Asterios Polyp is a fragile book whose cover is easily marred and which librarians say is hard to wrap in plastic. Why did he design the book the way he is?

It was “the most frustrating package I could come up with,” said DM, to much laughter. He wanted the final product to have a rawness to it.

What visual artists working outside the comics medium speak to him?

Loads. He is interested in artists that depict space, but also those who work in a “flat language” like Leger, Matisse and Picasso. Frida Kahlo. Velasquez. Saul Steinberg. Max Beckmann and Philip Guston were both formative influences in college. There was another artist that I didn’t catch.

At what point does experimentation enter the process of his creation–at the beginning, or is he continuing to experiment even later in the creation of the book?

The experimentation comes early on, not later. “Everything is about appropriateness.” He works out the book’s consistency ahead of time. For example, with Asterios Polyp, he had to settle on each characters lettering fonts and the size of that font before he began drawing or even considering the pictorial content of the book.

How has teaching influenced his approach to comics?

He began teaching in the mid-1990s. This was at a point where he wans’t doing much work “for various reasons.” The first class he taught was a 12-week general course on comics. Devising his syllabus meant he had to break his art down. He needed to determine what it does, how it works. This made him more analytic; he examined the medium from a distance. Stepping back from his art allowed him to consider what he does and doesn’t do. He also finds it interesting to see what solutions the students bring back from the problems he sets. Teaching provides him with a variety of responses to the question of “What’s a new way of solving this problem?”

What has his experience been like working with other writers?

Pretty good. He hasn’t done it much. There’s a lot of discussion and collaboration.

With City of Glass, he worked with Art Spiegelman as art director and Paul Karasik as writer.

This was an interesting collaboration. He realized that Paul Auster’s City of Glasswas not a very visual book. He asked himself “Why is this a good idea?” Then he realized that it was the very metaphysical nature of the book which made it a good idea. The work became an attempt to “visualize these things.” Karasik brought to the work his abstract thinking and visual metaphors. Karasik had a first crack at writing the book and even prepared sketches. An impasse was reached and DM came and helped fix what problems there were. He learned a lot from working with Karasik.

How did working on City of Glass demonstrate the difference between how DM and Paul Karasik think about comics?

This was in 1993, the time when DM was producing more physically grounded works like “Big Man.” Karasik hasn’t done a lot of work that people have seen, but his comics were about ideas. They used diagrams and visual metaphors. DM was picturing something in real space. The two artists met in the middle.

He’s worked with both Jim Shooter and Art Spiegelman. Can he account for his rapid evolution between mainstream and art comics?

It felt more like years …

His progress feels like a shedding of previous baggage, moving from a Gene Colan-inspired Daredevil to a naturalistic Batman …

His collaborators were usually surprised by what he was doing. He was fortunate on that level that they were understanding.

Most graphic novels are serialized first. Did he ever consider serializing Asterios Polyp?

No. It had to appear as a single book.

And that’s your lot. My apologies for any inaccuracies. I’m sure there will be audio and transcript available on other sites in the coming days, but I hope you enjoyed this precis.

Tags: Alex Toth, Art Spiegelman, Batman: Year One, Charles Schulz, Chester Gould, City of Glass, Dan Nadel, Daredevil, Dash Shaw, David Mazzucchelli, Ernest Hemingway, Fernand Leger, Frank Miller, Frank Santoro, Frida Kahlo, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Gene Colan, Henri Matisse, Jack Kirby, Jim Shooter, Jim Sternanko, Leger, Max Beckmann, MoCCA, Pablo Picasso, Paul Karasik, Philip Guston, Rubber Blanket, Saul Steinberg, Steve Ditko, William Faulkner

July 17, 2009 at 6:47 am |

Man, I wish i could of been there.

July 17, 2009 at 12:25 pm |

[…] [Scene] David Mazzucchelli in New York City Link: Squally Showers […]

July 17, 2009 at 12:55 pm |

Thanks for sharing this!

July 17, 2009 at 6:34 pm |

One correction, I think Batman was wearing a heavy cape and boots, not books.

Great piece, thanks for posting it.

July 17, 2009 at 6:43 pm |

Too tired to edit properly. Thanks for the catch, ADD. Will change it now. Still, I wonder what books Batman would have carried with him. Nietzsche, maybe.

July 17, 2009 at 6:46 pm |

[…] early artwork depicted characters concretely and realistically; as he mentions in a recent interview, it was working with Karasik on the Auster book that got him to approach the craft differently. […]

July 17, 2009 at 6:48 pm |

With all references to The Superman torn out, no doubt…

July 17, 2009 at 6:50 pm |

[…] aka present and future cartooning stars. We were going to type up a few notes, but INCREDIBLY, Squally Showers has typed up THE WHOLE THING, in record time. [Link via […]

July 17, 2009 at 7:02 pm |

Great article! Thanks. 🙂

July 18, 2009 at 1:50 pm |

thank you for posting this!

July 18, 2009 at 7:09 pm |

Thank you very much for this transcript, it was a very interesting read.

July 21, 2009 at 3:33 am |

[…] está publicada una transcripción indirecta y un audio completo de la esperada conversación de Dan Nadel con Mazzucchelli en el […]

December 1, 2009 at 3:58 am |

I love Mazzuccheli’s work. Especially “Batman: Year One”. I have yet to read Asterios Polyp, though I can’t wait to get it. Haven’t read City of Glass or Rubber Blanket either, though I should.

December 1, 2009 at 4:04 pm |

Dennis: Over the years, Mazzuchelli’s work radically changed from the Daredevil/Batman: Year One stuff you love him for. The progression took place mostly in the three issues of Rubber Blanket, which can be hard to find but it’s pretty interesting. Asterios Polyp does some really interesting formal experiments with color, shape, framing and layout in telling its story. It’s like watching an expert gymnast go through a particularly difficult routine, and highly recommended!